Solar + Battery Car DIY STEM Kit

$11.99$6.50

Posted on: Dec 14, 2004

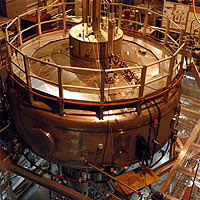

MIT and Columbia University students and researchers have begun operation of a novel experiment that confines high-temperature ionized gas, called plasma, using the strong magnetic fields from a half-ton superconducting ring inside a huge vessel reminiscent of a spaceship. The experiment, the first of its kind, will test whether nature's way of confining high-temperature gas might lead to a new source of energy for the world.

First results from the Levitated Dipole Experiment (LDX) were presented at a meeting of the American Physical Society the week of Nov. 15. Scientists and students described more than 100 plasma discharges created within the new device, each lasting from five to 10 seconds. X-ray spectroscopy and visible photography recorded spectacular images of the hot, confined plasma and of the dynamics of matter confined by strong magnetic force fields.

A dedication for LDX, the United States' newest approach to nuclear fusion, was held in late October. Fusion energy is advantageous because its hydrogen fuel is practically limitless and the resulting energy would be clean and would not contribute to global warming as does the burning of fossil fuels.

Scientists using the LDX experiment will conduct basic studies of confined high-temperature matter and investigate whether the plasma may someday be used to produce fusion energy on Earth. Fusion energy is the energy source of the sun and stars. At high temperature and pressure, light elements like hydrogen are fused together to make heavier elements, such as helium, in a process that releases large amounts of energy.

Powerful magnets, such as the ring in LDX, provide the magnetic fields needed to initiate, sustain and control the plasma in which fusion occurs. Because the shape of the magnetic force fields determines the properties of the confined plasma, several different fusion research experiments are under way throughout the world, including a second experiment at MIT, the Alcator C-Mod, and the HBT-EP experiment at Columbia University.

LDX tackles fusion with a unique approach, taking its cue from nature. The primary confining fields are created by a powerful superconducting ring about the size of a truck tire and weighing more than a half-ton that will ultimately be levitated within a large vacuum chamber. A second superconducting magnet located above the vacuum chamber provides the force necessary to support the weight of the floating coil. The resulting force field resembles the fields of the magnetized planets, such as Earth and Jupiter. Satellites have observed how these fields can confine plasma at hundreds of millions of degrees.

The LDX research team is led by Jay Kesner, senior scientist at MIT's Plasma Science and Fusion Center who earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1970, and Michael Mauel, a professor of applied physics at Columbia University who earned his degrees from MIT (S.B. 1978, S.M., Sc.D.).

'In a way science is a key to the gates of heaven, and the same key opens the gates of hell, and we do not have any instructions as to which is which gate.

Shall we throw away the key and never have a way to enter the gates of heaven? Or shall we struggle with the problem of which is the best way to use the key?'

'In a way science is a key to the gates of heaven, and the same key opens the gates of hell, and we do not have any instructions as to which is which gate.

Shall we throw away the key and never have a way to enter the gates of heaven? Or shall we struggle with the problem of which is the best way to use the key?'